New Year, New You and Why Change Is So Difficult

The Power of the Fresh Start Effect

Every year, millions of people set New Year resolutions with genuine intention. And every year, most of those resolutions fail. Research consistently shows that roughly 80 percent of New Year resolutions are abandoned by February, despite strong initial motivation (Norcross and Vangarelli, Journal of Clinical Psychology).

This failure is a predictable outcome of how our brains processes time, reward, and effort.

Behavioral science offers a clearer explanation for why change is so hard and what actually helps people succeed. When we understand these mechanisms, goal setting becomes less about force and more about design.

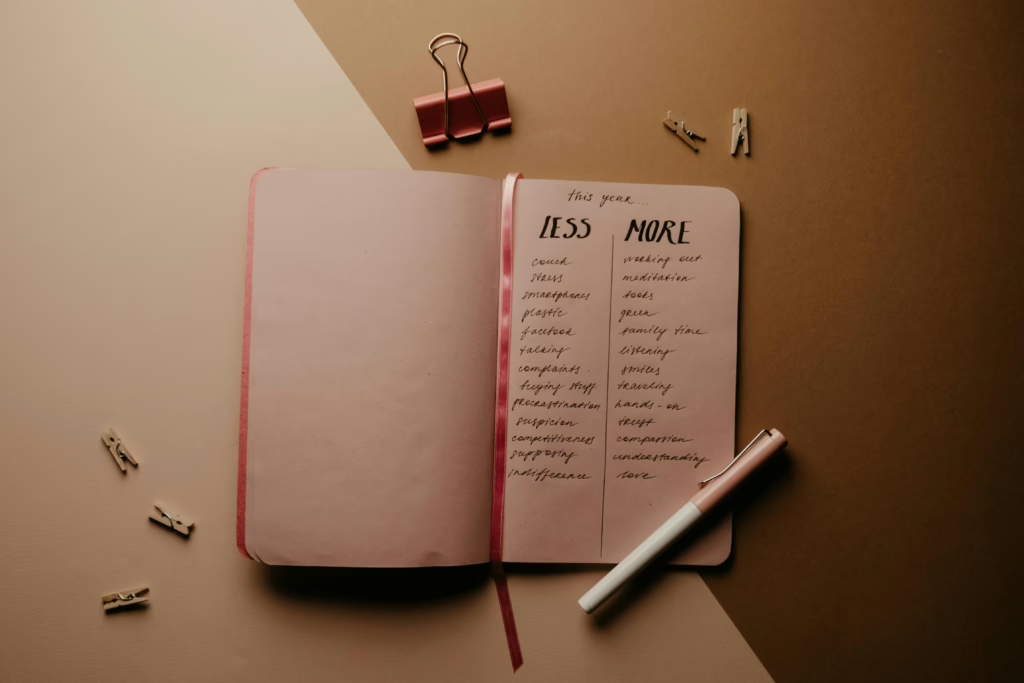

Behavioral scientist Katy Milkman and her colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania describe the Fresh Start Effect as our tendency to take action following temporal landmarks such as a new year, birthday, new job, or even the start of a week.

Importantly, fresh starts are not limited to January: They can occur whenever intention is paired with structure.

But regardless of when they start…they usually fail. Here’s why:

Why Our Brains Resist Change

One of the most important concepts in behavioral economics is temporal discounting. Temporal discounting describes our tendency to value immediate rewards more highly than future ones. The discomfort of effort today feels real and tangible, while the benefits of better health, more energy, or long-term wellbeing feel distant and abstract.

Extensive research shows that people systematically choose smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards, even when the delayed reward aligns with their stated goals (Laibson, Quarterly Journal of Economics; Frederick, Loewenstein, and O’Donoghue, Journal of Economic Literature).

This is why quitting something harmful or starting something beneficial feels so difficult. The brain is not optimized for future outcomes, rather it is optimized for short term certainty and comfort.

Habits compound this effect. Habitual behaviors are encoded in neural pathways designed to conserve energy. Once a behavior becomes automatic, the brain prefers repetition over change. Research in neuroscience and psychology shows that disrupting habits requires more than intention. It requires altering cues, routines, and rewards (Wood and Neal, Annual Review of Psychology).

Why Most Resolutions Fail

A review of goal setting research published in Health Psychology Review found that both overly ambitious goals and isolated small goals tend to fail. Large goals feel overwhelming and vague. Small goals without context lack meaning and staying power.

The most effective approach is what researchers describe as a goal hierarchy or goal network. This includes a superordinate goal tied to identity, intermediate goals that reinforce that identity, and subordinate goals that translate intention into daily action (Carver and Scheier, On the Self Regulation of Behavior).

When goals are structured this way, behavior change becomes more resilient because each action reinforces a broader sense of purpose.

When researchers examine the most common resolutions, the vast majority relate directly or indirectly to health. Physical health, weight management, nutrition, stress reduction, sleep, and energy consistently rank at the top (Statista; American Psychological Association).

This reflects a deeper truth. Health underpins nearly every other area of life. Cognitive performance, emotional regulation, relationship quality, and career outcomes are all strongly influenced by physical and mental health status (World Health Organization).

Why Small Changes Work Better Than Big Declarations

One of the most effective ways to counter temporal discounting is to shorten the time horizon. When a goal only requires commitment for today, the brain perceives the reward as closer and more attainable.

This is something I learned firsthand. Many people are surprised to learn that I used to smoke. I did not quit by deciding I would never smoke again. That framing felt too absolute and too overwhelming. Instead, I told myself I was quitting for one day.

Then I made the same decision again the next day. And then again.

By focusing on a single day, I reduced the psychological distance between effort and reward. Over time, those days accumulated into permanent change, not through willpower, but through identity shift.

Research on habit formation supports this approach. A widely cited longitudinal study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology found that habit formation depends on consistency rather than intensity, with small repeated actions leading to lasting behavioral change over time (Lally et al.).

Identity Based Goals Create Staying Power

Goals that align with identity are significantly more likely to be sustained. When people view behaviors as expressions of who they are rather than tasks they must complete, follow through improves dramatically (Oyserman, Self and Identity).

Identity based motivation changes decision making. Actions become affirmations of self rather than obligations.

Ask yourself not only what you want to achieve, but who you want to be.

Do you see yourself as someone who values vitality, clarity, and longevity? Or someone who protects their energy and health? Someone who moves through life with intention and does what they say they will do?

Identity shapes behavior long before motivation enters the equation.

Set Goals That Actually Work

Research and experience point to several principles that dramatically improve outcomes.

1. Anchor your goals to a broader identity based intention. Define the type of person you are becoming, not just the outcomes you want.

2. Choose goals that support multiple outcomes. Regular physical activity, for example, improves metabolic health, sleep quality, stress regulation, mood, and dietary choices, creating a compounding effect across systems (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health).

3. Break goals into time limited commitments. Focus on what you can do today rather than what you must sustain indefinitely. This reduces resistance and directly counteracts temporal discounting.

4. Design your environment to support success. Behavioral research shows that environment often matters more than motivation. Reducing friction for desired behaviors and increasing friction for unwanted ones consistently improves adherence (Thaler and Sunstein, Nudge).

Moving Forward With Intention

True change is cumulative, and often invisible in the early stages. But over time, small consistent actions reshape identity, health, and quality of life.

The real question is what systems you are building, what identity you are reinforcing, and how intentionally you are working with human nature to set goals that last.

Fresh starts are powerful! Sustainable change comes from understanding how behavior actually works and designing your life accordingly.